Sensationalism Across Church History

Sensationalism is skewed or emotionally provocative presentation that maximizes audience engagement at the expense of accuracy and depth. It comes from secular media, to be sure, but religious contexts as well. For Christians, this can look like pursuing reactions, platforms, and experiences over the hard work of following Jesus and teaching others to do the same.

From the early church to modern times, there have been recurring cycles of emotional appeals, apocalyptic fervor, and spiritual manifestations—each good things—that went too far. The following traces examples of sensationalism across Christian history.

[This is a companion piece to “Sensationalism: What It Is and Why It Matters”]

Montanism (172 AD)

Soon after Christ in Phrygia (now central Turkey), Montanus and his prophetesses Priscilla and Maximilla began issuing ecstatic, “new” revelations of the Holy Spirit, claims that implicitly overrode the apostles’ teaching. Renowned church leader Tertullian—who actually coined the term “Trinity”—initially hailed a revival of apostolic power but later criticized its unchecked fervor; the historian Eusebius likewise denounced their excesses. By the early third century and ever since, virtually every major Christian tradition had condemned Montanism as heresy for asserting revelation beyond apostolic and Biblical witness.

This early controversy established a pattern we still see today: the tension between established doctrine and claims of new, direct revelation that either directly or implicitly (indirectly, subtly) supersedes. Because it has an inherent “marketing sizzle” to it, we can count on this strand of sensationalism coming back again and again.

The Medieval Period (c. 500-1500 AD)

During the medieval period, sensationalism often took the form of vivid, fear-based preaching about eternal judgment. Preachers would use graphic descriptions of hellfire and divine wrath to motivate repentance.

In the late Middle Ages, popular faith exploded into blockbuster spectacles: massive street processions with gilded floats, community passion-plays reenacting Christ’s suffering, dramatic flagellant (self-whipping) movements where penitents publicly scourged themselves in bloody displays to avert divine punishment, and charged friar sermons filled with lurid visions of hell. Though in some places these came from authentic devotion, methods often relied on hyped-up fear and shock value.

Revival Movements and Pentecostalism

Revival movements throughout church history have balanced authentic spiritual renewal with sensationalist tendencies. Crowds have often been swept up by demonstrations: mass emotional responses, outlandish prophecy claims, and sometimes staged healings that collapsed under scrutiny. While genuine transformation occurred across many times and places, these movements also produced problematic excesses:

- false prophecies that left followers disillusioned

- financial exploitation tied to altar calls (or false prophecies)

- emotional manipulation that bordered on mass hysteria

- and even instances of physical harm

It has taken the form of snake handling in Appalachia, mass "slaying" under emotional drums, and theatrical faith healing services where suggestion and crowd psychology sometimes played a larger role than divine intervention.

In response, denominational bodies later intervened with stricter oversight, accountability councils, and more measured worship practices to rein in the sensational and protect the integrity of authentic faith and moves of the Spirit.

End Times Theology and "Newspaper Exegesis"

Throughout church history, "newspaper theology" has been a persistent form of Christian sensationalism. This approach interprets current events—wars, natural disasters, technological developments, or political shifts—as direct fulfillments of biblical prophecy, especially from apocalyptic texts like Daniel, Ezekiel, or Revelation.

This pattern intensifies during periods of social upheaval. The World Wars sparked waves of prophetic speculation, with various leaders identified as Antichrist figures. Even today, some of the top performing online content asks if Trump, Elon Musk, or Obama is the antichrist.

The Cold War era saw nuclear threats interpreted through Revelation's imagery. More recently, the COVID-19 pandemic generated theories connecting vaccination programs to "the mark of the beast.”

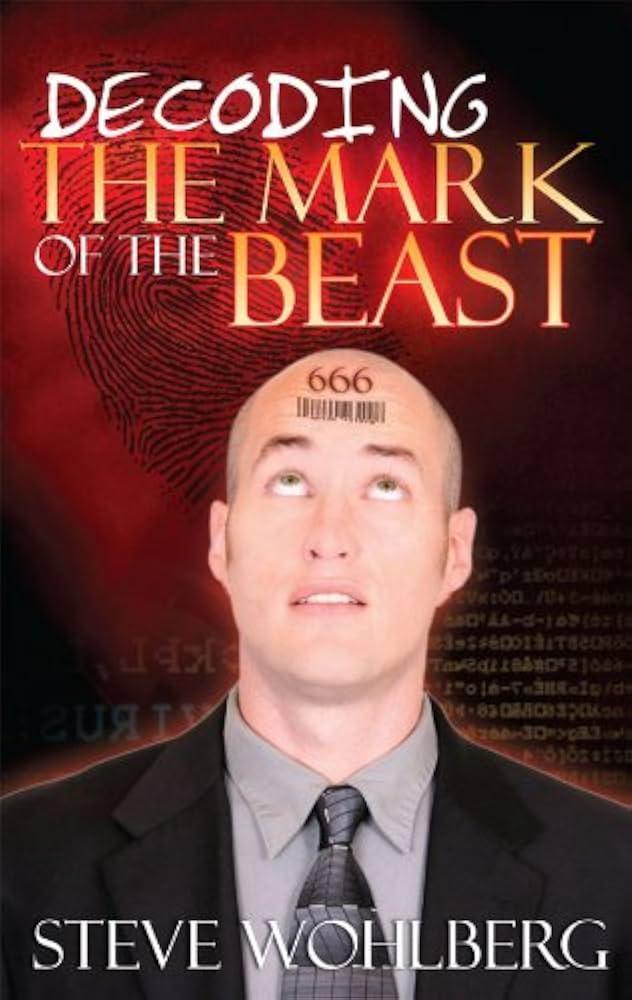

An Example of Prophecy Recycling: COVID-19 and Supermarket Barcodes

But the COVID-19 pandemic isn’t at all the only cultural event labeled “the mark of the beast.” For the launch of the Universal Product Code (UPC) in the mid-1970s, Christians who practice “newspaper theology” treated Revelation 13:16-18 (“mark … without which no one may buy or sell…666”) as an omen for their personal moment. In 1974, protesters had signs with “666” on them, foretelling the coming day when barcodes would be etched onto their foreheads.

What makes this form of sensationalism particularly problematic is its cyclical nature. Each time was heralded as history’s unique fulfillment of the text—yet the passage was simply being recycled, not fulfilled anew. When one prediction fails, proponents simply recalibrate their interpretations to fit new headlines, with little accountability for past errors. This creates a perpetual market for books, conferences, and media content promising to decode current events through prophetic lenses.

This approach often:

- Simplifies complex geopolitical realities into spiritual narratives

- Creates unnecessary fear and anxiety among believers

- Distracts from Christ's call to present faithfulness, regardless of the timeline

- Damages Christian witness when highly publicized predictions fail

More measured approaches see that the truth lies somewhere in the middle of newspaper theology and total disengagement from prophetic texts. Healthy end-times theology neither obsessively maps every headline to Revelation nor dismisses God's active guiding of history toward real, physically tangible conclusions.

It also doesn’t hurt to know some history—whether Y2K or the formation of the European Union, the 1918 Spanish Flu or the World Wars.

The Recurring Pattern of Failed Predictions

Despite Jesus's clear statement that "about that day or hour no one knows" (Matthew 24:36), each generation seems irresistibly drawn to predicting Christ's return.

William Miller's prediction of Christ's return in 1844 led to the "Great Disappointment" when thousands of followers sold possessions and waited on hillsides, only to face crushing disillusionment. Similar patterns emerged with Harold Camping's widely publicized predictions for May 21, 2011, which garnered international media attention and millions in promotional spending before failing.

These predictions typically share common elements:

- Complex mathematical calculations based on biblical numbers

- Selective reading of prophetic passages removed from their context

- Claims of special revelation or insight unavailable to previous generations

- Urgent calls for preparation that often involve financial decisions

- A curious blend of certainty about the timing yet flexibility in adjusting when dates pass

The damage goes beyond mere embarrassment to devastating spiritual casualties—people whose faith is shattered when sensational leaders and frameworks collapse. They also provide ammunition for skeptics who mock Christianity as fundamentally irrational, and they distract believers from Christ's actual instructions about His return: to remain faithful, watchful, and engaged in kingdom work regardless of the timeline.

More responsible approaches to Christ's return emphasize the biblical "already/not yet" tension—acknowledging that while Jesus will indeed return physically as promised, our focus should be on faithful living in the present. As theologian N.T. Wright notes, "The point of the Second Coming is not to predict when the world will end, but to tell us that the world as we know it is not God's final plan."

A Parting Caution For Those Seeing Sensationalism Mostly Elsewhere

It's important to note that sensationalism isn't limited to certain traditions within Christianity. While charismatic-leaning voices and movements have naturally had inherent risks, there has also been sensationalism among those who deliver scathing critiques of the places there’s been excess. Both the more emotionally-driven and intellectually-driven have sinful tendencies and environments which can easily rationalize harm, whether in words themselves or in stylistic approaches.

Charismatic sides have tended to overemphasize dramatic spiritual manifestations and experiences, but more liturgical and conservative branches have also tended to overemphasize cultural decline or push the Biblical doctrine of judgment in unhealthy framings.

Authentic movements of God often include deep emotion, energizing leaders and powerful words and experiences. The challenge is discerning between genuine spiritual vitality and manipulative sensationalism.

This line is not black-and-white.

Only the wisdom of God can parse through it, and many faithful followers of Jesus will come to areas of disagreement. That’s okay. In areas like this, it’s critical to find unity on essential beliefs and recognize where differences are more to do with perception, style, or opinion.

Conclusion: Learning from History

This historical perspective offers us wisdom for navigating today's digital landscape, where sensationalism is amplified by algorithms designed to maximize engagement regardless of truth or spiritual benefit.

These historical patterns reveal that sensationalism is not unique to our digital age but has manifested throughout church history whenever new communication methods emerge or social anxieties intensify. By recognizing these repeat cycles, today's followers of Jesus can develop discernment, neither rejecting emotional expression nor blindly embracing claims.

Throughout all cycles, the church has repeatedly needed to recover balance, returning to Scripture's call for both spiritual passion and sound teaching—both desiring to resonate with the lost and spiritually immature and committing to the hard work of true discipleship.

The lessons of history call us to a balanced faith that honors both heart and mind and seeks truth over spectacle in an age defined by the latter.